Behind the scenes of London Rabita Committee

For the public, it may appear that the all-powerful Altaf Hussain has the last word on everything decided at the MQM office in London, but a visit to the party’s UK secretariat shows there are other players working from behind the scenes.

The most prominent of them all is Nadeem Nusrat, who was made the convener of the MQM Rabita Committee in a quiet and unceremonious move in October, 2015. This committee is the policymaking, central body of the MQM watching over the party’s Karachi leaders.

In Nusrat’s own words, ‘convener’ is the highest position in the party structure of the MQM. Towering above parliamentarians and prominent faces of the MQM, Nusrat is therefore highest in command in the party’s strict organisational structure, filling in the shoes of slain Dr Imran Farooq, who held this post till 2008 before he parted ways with the party. On September 16, 2010, Farooq was stabbed to death in London.

Until January 2016, Nusrat was referred to as the ‘qaim maqam’ [acting] convener but his title was made permanent at the start of this year, effectively making him a prospective successor.

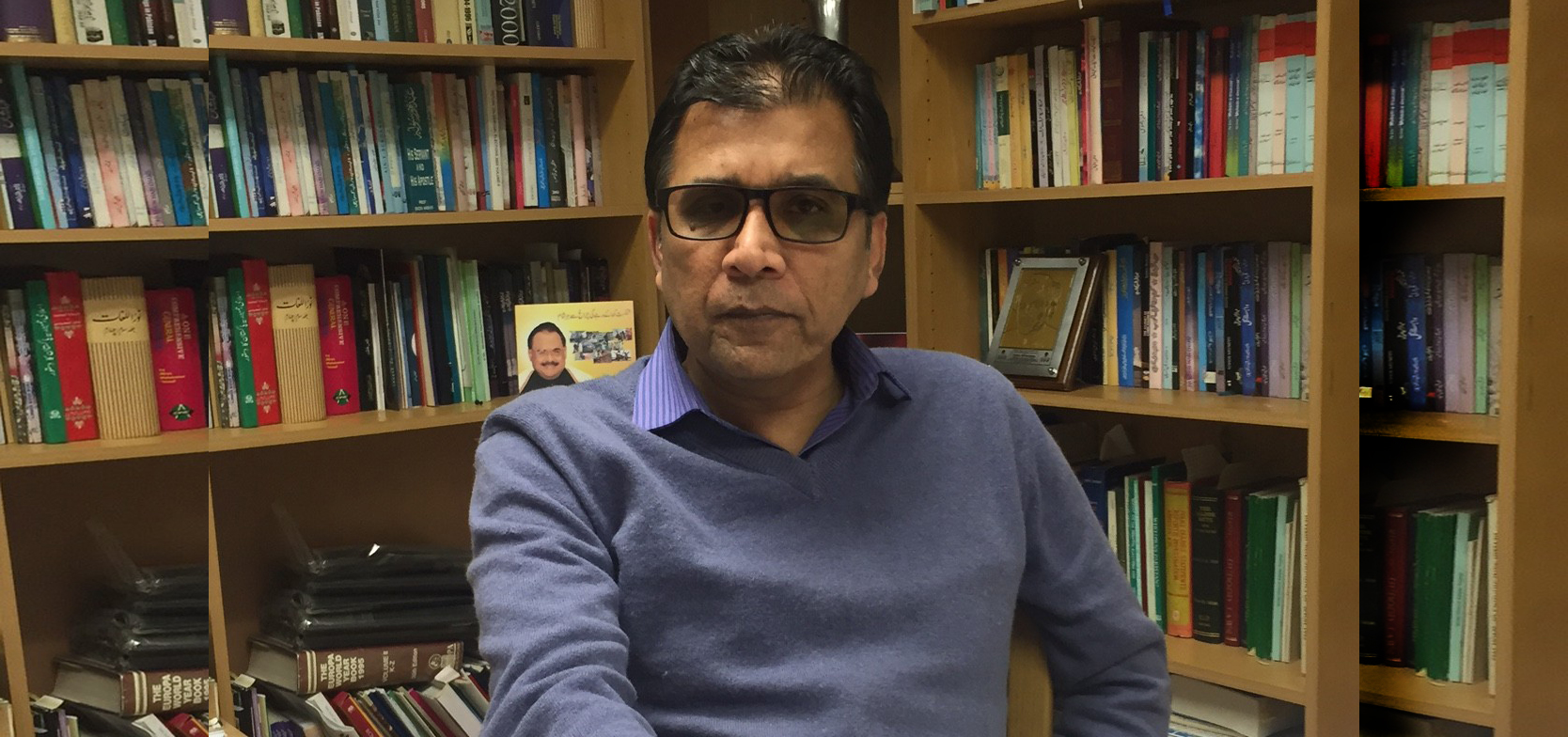

It was a cold London night in November 2015 when chilly winds dropped the temperature and Nusrat sat down to talk to The Express Tribune about holding the reins to arguably the third most popular political party in Pakistan. The MQM’s International Secretariat located among the hustle and bustle on Edgware’s high street occupies the entire first floor of the building. Inside, Nusrat warmed himself with a cup of hot beverage.

Unlike other party leaders who hog public limelight, Nusrat chooses to work from behind the scenes. He shies away from the media, appearing on only selective talk shows. At public events and meetings, he prefers to be a backbencher.

Nevertheless, the new convener has brought changes within the MQM with its constitution being rewritten and considerations of intra-party elections. The 42 departments and wings of the party have been cut down to 26. Young men and women are being encouraged to step forward.

Nusrat’s political journey

January 2016 marks 24 years of Nusrat’s self-exile in London. His political journey goes back much earlier to 1983 when he was a student of class nine and was encouraged by his cousin to join the All Pakistan Mohajir Students’ Organisation (APMSO) – a student wing that eventually laid the foundations of the MQM.

His family had been disillusioned by the economic and political crisis of that time and had been feeling alienated. His father’s textile business suffered at the hands of nationalisation. “The ground was already fertile,” he said. “We are mohajirs [migrants] from Hindustan and Urdu-speaking. It wasn’t hard for me to join the APMSO.”

The young recruit of the APMSO had to prove his worth among the zealous young men eager to fight for the rights of the mohajir community. “It was a challenge. There were mixed responses from other members,” he recalled.

The first time he met Altaf was at the funeral of an office bearer in Landhi. He remembered how Altaf remarked that it was good to see young people when they met. As in-charge of MQM’s Landhi Unit No 84, Nusrat campaigned aggressively when the MQM contested for the first time the local government elections of 1987. The party achieved an overwhelming victory and Farooq Sattar became the city’s youngest mayor.

In the same year, at the age of 20, Nusrat became a political secretary for Altaf, which brought him closer to the party chief. He recalled several discussions the two would have about politics and human psychology. Nusrat’s responsibilities included taking notes, listing down political appointments and talking to the media. He did, however, keep a low profile and kept his distance from organisational matters.

During this time as an active political worker, Nusrat was juggling his studies in the economics department at the University of Karachi, and his responsibilities towards his parents and eight siblings.

Thus, from 1987 to 1992, Nusrat lived with Altaf at Nine Zero along with Dr Imran Farooq – the men sleeping in the three rooms situated on the rooftop. They started working at 10am and would work throughout the day until midnight. Nusrat visited his family once a week, sometimes only once a month.

Those were the times when Altaf was at the height of his fame but was easily accessible to his supporters. Nusrat remembers the MQM chief throwing away used tissues at the crowd, leading to a fight between supporters to grab them. Altaf even handed out Rs10 notes with his autograph, he said. “Working for Altaf gave me tremendous joy.” The convener has penned down a manuscript on Altaf’s life which has yet to be printed.

Nusrat remembers the MQM chief throwing away used tissues at the crowd, leading to a fight between supporters to grab them. Altaf even handed out Rs10 notes with his autograph, he said.

The euphoria was, however, too good to last. MQM’s senior leaders Afaq Ahmed and Amir Khan left the party. “It was a huge shock when Afaq and Amir left the party, especially Afaq, whom I knew well,” said Nusrat.

An assassination attempt at Altaf on December 21, 1991, led to his decision to leave the country. Nusrat left six days after Altaf did in January 1992, joining him first in Saudi Arabia and then departing for the UK. “I had packed my stuff for only three to four weeks,” he admitted. “I thought I would be able to go back soon. I had my whole family there.”

Starting from scratch

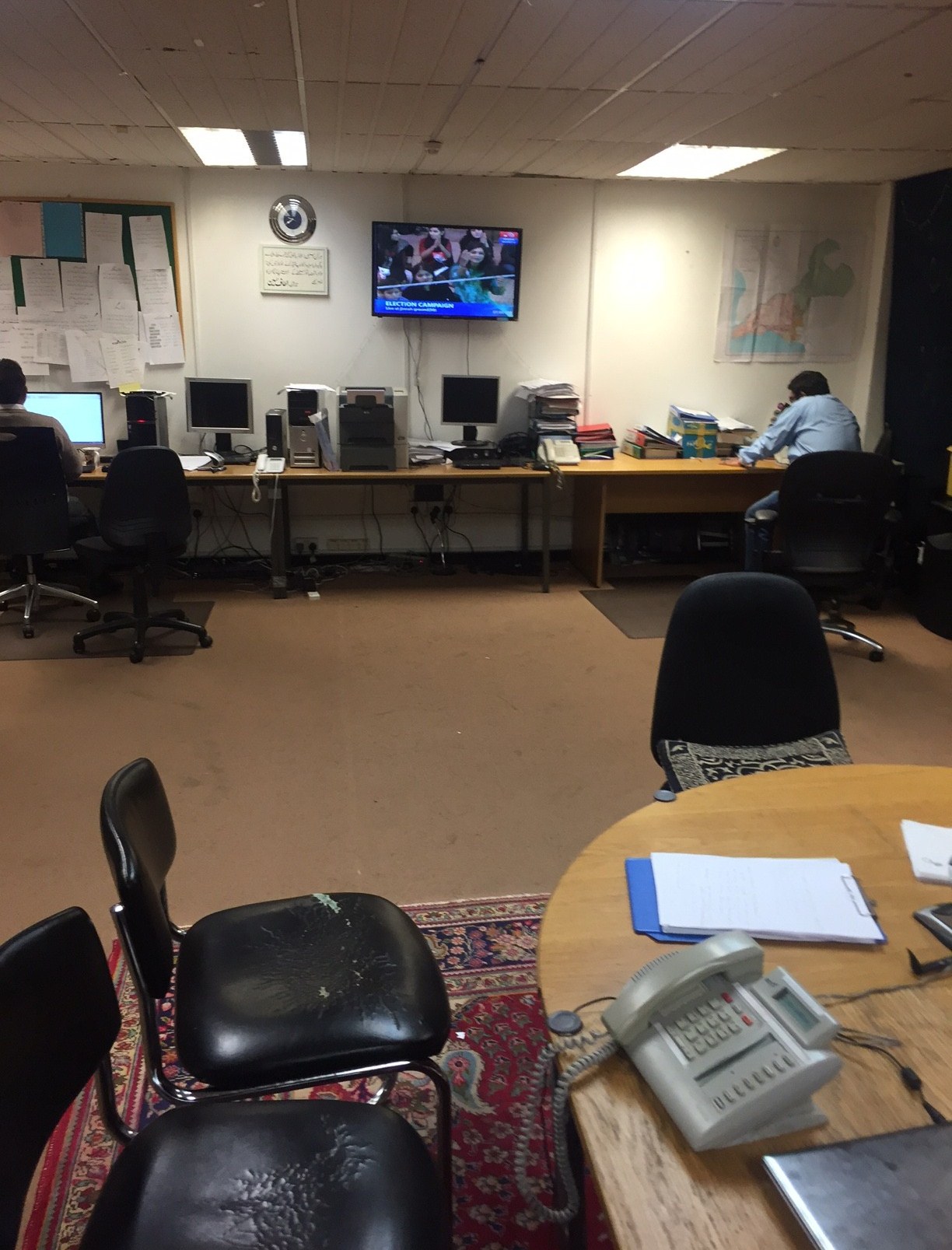

In London, the party had to start from a scratch amid feelings of helplessness and anger, and dwindling finances. Their first office was a room belonging to another MQM leader Mohammad Anwar’s accounting office.

Slowly and steadily, the party got on its feet. In between for several years, Nusrat went to the US, where he taught history and English literature at schools. His wife, a party worker, was chosen by Altaf himself.

In 2013, he returned to the UK and became the deputy convener. Later, he became a senior deputy convener and was eventually chosen as the convener in 2016. A Master’s graduate from Birkbeck, University of London, in History and Political Science, Nusrat shared that he is passionate about history, especially American history and the politics of the subcontinent. He loves reading, his favourite being Dark Continent by Mark Mazower and Ibne-e-Safi’s Imran Series.

Role of a convener

As a convener today, Nusrat gets reports from Nine Zero and the various MQM zones. His work day often lasts up to 12 hours every day. He consults with other Rabita Committee members but enjoys the powers to overwrite any decision. MQM’s numerous wings, such as the ones for labour and women, also report to him. He’s also in-charge of the international secretariat in the UK, where the party claims to have 1,000 workers.

Mustafa Kamal’s departure

Long before Mustafa Kamal returned with his explosive allegations against the MQM chief, Nusrat recalled in November 2015, the circumstances around Kamal’s departure. “I was the last person whom Mustafa Kamal spoke to,” he said. “He called me up and said that his wife and children have left, and he has to go and get them. But he never came back.”

Kamal later emailed the party, and informed about having family troubles. “He never explained why. He never shared what went wrong. Mustafa left in a crisis.”

I was the last person whom Mustafa Kamal spoke to,” Nusrat said. “He called me up and said that his wife and children have left, and he has to go and get them. But he never came back.

Nostalgia for Karachi

It is impossible to separate Karachi from him, said Nusrat, getting sentimental as he shared how he missed the Ramazan of Karachi, the phehni (vermicelli) he used to eat for sehri and the congregational taraweeh prayers, and the festivities of Eid. Since his departure in 1992, he met his two sisters for the first time in Saudi Arabia.

For now, Nusrat continues to live in London. He felt that it was not safe to return home. “The situation is not conducive. The environment is hostile. There are cases,” he said.

Living a life in self-exile has been hard. This January marks 24 years, and Nusrat feels it is a sacrifice. “It’s a big sacrifice but nothing [compared] to [the ones given by] people who lost their lives.”