Cutting the [telephone] cord

The man who had the power to shut down a city 4,000 miles away in mere minutes and bring to tears thousands assembled in a different continent has lost his connection.

2015 was a difficult year for Altaf Hussain, just as it was for his party, the Muttahida Qaumi Movement (MQM). But more than the arrests and raids of his workers, it was his words that did most of the damage. His tirade and frustration was mostly a result of the Rangers operation in Karachi, which the party claimed was solely targeting their supporters.

In the year 2015, we heard Altaf roar and condemn forbidden territories -- the army, the establishment and the judiciary -- all in one breath. We saw assemblies passing resolutions against him and politicians calling him a traitor. We saw the armed forces taking offence by him and local courts declaring him an absconder and issuing non-bailable warrants for his arrest. We saw him interrogated by Scotland Yard. And we saw him stepping down and then back up, multiple times.

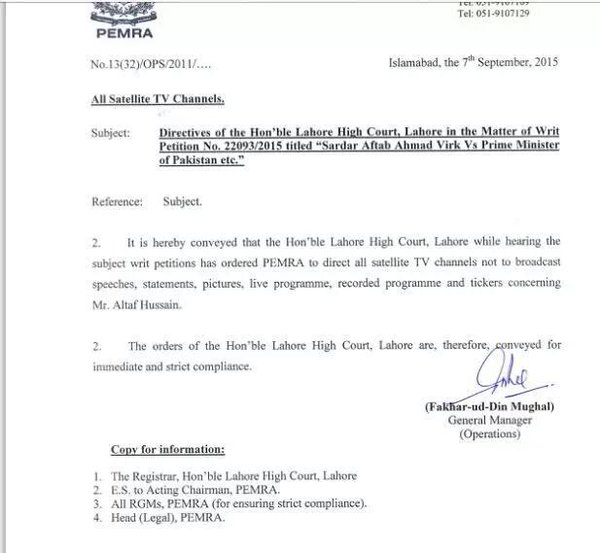

Eventually, we saw him being silenced when the Lahore High Court (LHC) imposed on August 31, 2015, a ban on the media from giving live coverage to his speeches. The decision was upheld by the Supreme Court. His voice disappeared from our television screens and his words no longer found space in newspapers.

A rollercoaster ride

The year began with Altaf announcing his resignation from the party after the ‘extrajudicial’ killing of an MQM worker. A month earlier, he had opposed the establishment of the military courts, saying it was better to impose martial law.

Following the March 2015 raid at Nine Zero, Altaf accused the paramilitary force of bringing weapons wrapped in blankets only to ‘recover’ them as the party’s arsenal.

His veiled threats included instructions for young party workers to prepare for commando training.

The same week, Altaf lashed out against the Rangers during a live interview with a television channel. “The officials who raided my house were Rangers officials. They ‘were’. They are now ‘were’ [of the past],” he said. These threats did not sit well with the Rangers, whose spokesperson filed a case against Altaf for threatening them.

For the first time, the political kingpin was being questioned and his character tarnished, especially in the aftermath of a report published in a foreign publication. In June 2015, BBC published a report, based mostly on quotes from anonymous sources, claiming that the MQM received funding from India. A few days later, Altaf was accused of asking for help from India.

Not one to cower in the face of opposition, the MQM chief launched into a tirade against his local allies. He accused his long-time political ally Pakistan Peoples Party co-chairperson Asif Zardari of registering cases against him and for giving Rangers a licence to divide Sindh.

Effectively putting an end to his tirades, in August, the LHC directed the Pakistan Electronic Media Regulatory Authority (Pemra) to ban the broadcast of Altaf’s speeches and prevent print and electronic media from publishing his photos. The ban continues to this day despite several attempts by the party to appeal against the verdict.

His face and his voice may have disappeared from our television screens but the ban, it seems, worked in favour of the MQM as it was able to sweep the local government elections in Karachi in December, earlier clinching a victory in the NA-246 by-elections.

MQM minus Altaf?

Back when Altaf was still gracing our television screens, he often repeated his claims that some officials in Pakistan’s security establishment wanted the MQM to continue working but without him. He called it the ‘minus one formula’.

Altaf’s political role in the country declined significantly by the end of 2015 but there are many factors that contributed to this, such as his deteriorating health and the media ban on his speeches. And it was due to these reasons perhaps that, for the first time, Altaf gave hints about potential successors to the MQM throne. The names of Dr Farooq Sattar and Nadeem Nusrat were thrown around, along with plans to form a 50- to 60-member Rabita Commitee in London and Karachi.

Political analyst Hasan Askari agrees that the MQM chief has been pushed to a corner but, he added, Altaf would remain a symbolic head. “He continues to be an important symbol but [it seems] his operational capacity has been reduced,” he said.

Party leaders, too, are adamant that there is no MQM without their chief. MQM’s victory in the elections was Altaf’s victory, and the two are inseparable, said MQM leader Dr Farooq Sattar with speaking to The Express Tribune. “MQM and Altaf are sine qua non, Lazim wa malzoom.”

Living in exile

Altaf’s office in London has a black chair and a brown wooden table. His pharmacy degree from the University of Karachi hangs on the wall, along with pictures of his daughter, Afza. The bookshelves carry Maulana Maududi’s translations of the Holy Quran and Nelson Mandela’s biography Long Walk to Freedom.

This office is only used on the rare occasions the party chief visits. The last time he graced the office was on the party’s foundation day last month. January 2016 marks 24 years of Altaf’s self-exile in London, a life he now spends confined to his house in Edgware. He fled Pakistan in 1992 after an assassination attempt and has never returned, fearing for his life.

But even 4,000 miles away, the fear of death continues to haunt him.

“He doesn’t go out anywhere fearing he would be killed like Dr Imran Farooq,” said an MQM leader, who recently paid a visit to Altaf. “There are threats to him. He stays at home.” Every time the political kingpin leaves his house, either to visit the hospital or to the party’s London secretariat, the London Metropolitan Police are informed.

Very few people, other than one or two MQM senior leaders and Altaf’s cousin, Iftikhar Hussain (who was interrogated by the Scotland Yard for Dr Imran Farooq’s murder but was released later), have access to his redbrick house, which is guarded by Caucasian bodyguards.

These physical barriers to entry, however, never prevent Altaf from communicating with his workers. He is known to use Facetime on his iPad to speak to MQM leaders, both in London and in Karachi. Sometimes, he calls a sector or unit in-charge for details of their work. During the election campaign, he is said to have written letters to workers to ask for their support.

Despite speculation that Altaf would be arrested in the money laundering case, the police bail was cancelled and now there is talk that the case might be dropped altogether.

And with the MQM back in the assemblies, together with its own mayor in three cities, and a possible understanding with the Rangers, the party sees a bright future for itself. “A new journey is beginning,” said Dr Sattar. “There is optimism, new vigour, new energy, new strength.”

However, this year presents a new challenge in the form of Mustafa Kamal and his seemingly ‘Minus Altaf’ formula.