Devolution of power within MQM

The Muttahida Qaumi Movement (MQM) is one of the few political parties in the country that has a well-organised internal structure, with power and accountability devolving right down to the streets. With 26 sectors and over 200 unit offices spread all over Karachi, the party boasts it works like a well-oiled machine – a claim corroborated by the manner in which it can shut down the city instantly. But since the start of the Karachi operation in September 2013, cracks have started to develop.

According to the MQM, ‘thousands of raids’ have been carried out at their sector and unit offices, along with the homes of party workers. The outgoing year 2015 only saw an increase in the intensity of this operation. In between the threats and raids, dozens of units and sectors were shut down for days, dismantling MQM’s micro-nerve centres of political activity.

The birth of MQM

The foundation of the MQM goes back to 1978 with the formation of the All Pakistan Mohajir Students Organisation (APMSO), a student group in the University of Karachi. By 1984, the APMSO gave birth to a political party, the Mohajir Qaumi Movement, which eventually rebranded itself into Muttahida Qaumi Movement to transcend its ethnic base. The same year, the party developed an internal organisational structure to take its politics to the grass-root level.

“The party studied the organisational structures of Jamaat-e-Islami and the Pakistan Peoples Party, and decided to come up with one of its own,” explained senior MQM leader Aminul Haque.

The founding members, including Altaf Hussain and Tariq Javed, designed a centralised party setup that penetrated deep into the masses through these sectors and units. Some even believe it took inspiration from communist parties.

The smallest party entity is a ‘unit’, which serves as the most important and effective office in getting party messages across to the people. Several units make up a ‘sector’.

Before the 1992 operation, the units reported to sectors, which reported to zonal committees, which were answerable to a 10-member Tanzimi Committee (organising body) that included MQM chief Altaf Hussain, chairperson Azeem Tariq, Dr Imran Farooq and others.

In the early days, the party’s structure within Karachi was divided into three zones: A, B and C. Zone A included areas of Landhi, Malir, Shah Faisal, and was headed by Afaq Ahmed. Zone B comprised PIB Colony and adjacent areas that were led by Shahid Khan, and Zone C included Liaquatabad, Nazimabad, New Karachi, which were led by Amir Khan. Later, zones D and E were also added.

The party’s sectors and units suffered during the 1992 operation as well. Many of them were shut down, at least for public dealing, and were only able to resume activities nearly a decade later. The zonal committees never reappeared.

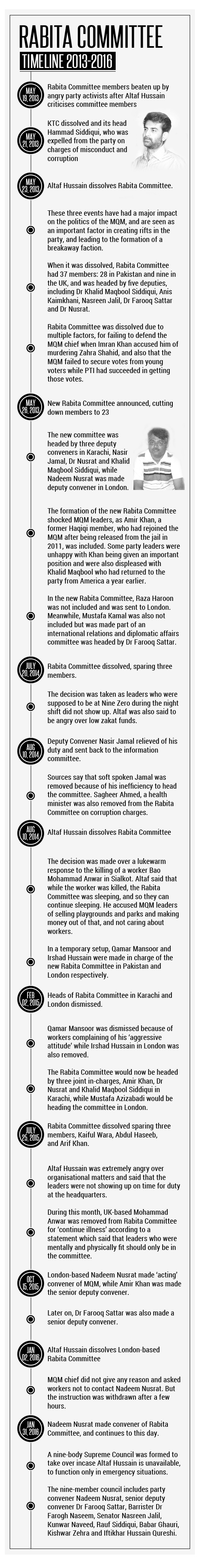

In 2002, the Karachi Tanzeemi Committee (KTC) was formed to oversee the party’s sectors and the units. In September 2014, KTC was completely disbanded. The sectors and units report to the Central Executive Council and the Rabita Committee.

Each unit and sector is headed by a unit in-charge and a sector in-charge, respectively. Each sector has a finance secretary and nine sector members, along with its in-charge. Each office opens in the evening when the party workers return from their day jobs. The party claims that all these men work voluntarily but they are required to give a certain percentage of their salary towards the Muttahida Qaumi Fund, a workers’ fund that is used to run the sector offices.

MQM MNA and MPAs are also required to spend time at sector offices and deal directly with complaints shared by residents. The duties of MQM sectors and units include running election campaigns, arranging public meetings, mobilising people, collecting donations, inducting new workers and spreading the party message.

Senior MQM member Aminul Haque explained that the sector and unit offices were established in areas where they felt there was a need. He called the Federal B Area sector, which oversees 13 units, and the Nazimabad sector, which oversees 12 units, two of their most important offices.

At the start of this year, the party decided to rename its internal organisational structure to get rid of the negative image associated with its sectors and units. Units became ‘union committees’ while sectors were renamed ‘towns’.

Hotbed for militancy?

Time and time again, MQM’s sectors and units have been accused of being involved in criminal activities and running a network of militants. In the early 1990s and during the last decade, MQM’s sectors and units became very powerful. The sectors in-charge became men that were dreaded and feared by residents and even policemen, and often considered to have the same clout as the local police station house officer (SHO).

People who wished to get a new utility connection or hold a function on amenity land would bribe the sector or unit in-charge for permission. Once the payment was made, people were guaranteed that everything would run smoothly.

The formation of units and sectors has also remained controversial as the party has often been accused of building their offices on parks and amenity plots by illegally encroaching and occupying land. But, more dangerously, members of units and sectors have been arrested on charges of target killing, extortion and street crimes.

“There has been militancy on an individual level by members of [our] sectors but it is not our policy to promote violence,” said one MQM leader, who requested anonymity.

The head of MQM’s KTC, Hammad Siddiqui, was sacked from the party in 2013 after he was accused of land grabbing, ‘china-cutting’ and attacking activists of Sindhi nationalist parties. Siddiqui is also suspected to have played a key role in the May 12, 2007, violence in Karachi, and of running a network of target killers.

In 2015, Rangers issued a press release on their raids at MQM offices in which they made similar accusations. “MQM’s organising committee (KTC) empowers its militant wing, which is why its sector and unit in-charges are being arrested,” the statement claimed.

The same year, several sector and unit heads were put behind bars. Sector in-charge Rafiq Rajput was arrested from his house by Rangers for his alleged involvement in the May 12 carnage. He was also accused of running a network of hit-men. However, Rajput is currently in Karachi Central Jail on just one charge of possessing an illegal weapon.

Baldia Town sector in-charge Rehman Bhola, who has yet to be arrested, has been accused by another party member of setting the Baldia garment factory on fire, in which more than 250 people were killed.

Landhi sector in-charge Rukunddin was arrested for hiding weapons. A former Ranchore Line sector in-charge, Amir Ali, has been accused of murders and an attack on nationalists.

Among all the sectors spread across various neighbourhoods in Karachi, Liaquatabad and Korangi sectors had the most raids. The MQM claimed that several innocent men were arrested, brutally tortured and some were killed in custody. A unit incharge, Faisal Khan, is still missing.

Federal B Area sector in-charge Farhan Hashmi was picked up by the Rangers in August while on his way to Nine Zero. He was released a few days later but he, like other MQM men who survived the detention, refused to share his experience during custody. “Even a single day with the Rangers was enough,” was all he said with a small smile, while speaking to The Express Tribune.

Aftermath of a raid

There was urgency in the air on that August night as the gates to the MQM’s Mehmoodabad sector office were flung open for MNA Ali Raza Abidi and his bodyguards. The gates lead into a courtyard and a few rooms. There were at least half-a-dozen people standing to receive him, dread visible on their faces. This sector office had opened merely a few days ago but many party supporters preferred to stay away.

Abidi made his way into one of the offices before he started meeting residents who came by with various applications, complaints and requests ranging from water scarcity in the neighbourhood to family disputes. This is common practice at the MQM’s sector offices spread across the city but these services were stopped following raids at these sector and unit offices.

“It used to be more crowded before,” said Abidi. The Mehmoodabad sector office oversees six units and manages between 3,500 and 4,000 workers. “People are scared to come near the sector offices now.”

Sindh Rangers had raided this particular office in February 2015 and would do so again in September that year. The first raid saw paramilitary soldiers breaking into the office late at night, taking away with them party pamphlets, record files, hard disks and even “Altaf bhai’s pictures”, much to the chagrin of a young worker.

The second time they came was during Eidul Azha, a time when party activist work overtime to collect sacrificial hides, which are then sold to tanneries at high prices. Abidi was present in the sector office when the Rangers came. They wanted to check if the party had permission to collect hides.

Women take charge

As law enforcers swooped down on sector offices, there came a time in 2015 when the party’s female workers — referred to as ‘bajis’ (elderly sisters) among party ranks — and elderly men started taking charge of these offices from its young, aggressive men. Najma Iqbal, a former councillor, spent many of her evenings in one of the sector offices. “Family is important but so is Altaf bhai. I was there for him,” she said.

She would come in the evening and stay till 10pm, carrying out the same tasks as MNA Abidi in his Mehmoodabad sector office. Many people came to her to complain about the persistent water shortage, some women came to her with problems with their in-laws. As she mentored these troubled women, Iqbal encouraged them to attend party rallies.

Musarrat is another baji who took charge when the operation intensified. “The party needs us,” she said, explaining that she helps by trying to woo female residents into participating in the activities at sector offices.

The situation has improved since the MQM re-joined the National and provincial assemblies. The sector and unit offices reopened and the party’s clean sweep of the local government elections returned the same hustle bustle to the party’s grass roots.