A Jewish woman’s memories of Lahore

Hazel Kahan recalls the city 40 years after she left with her parents

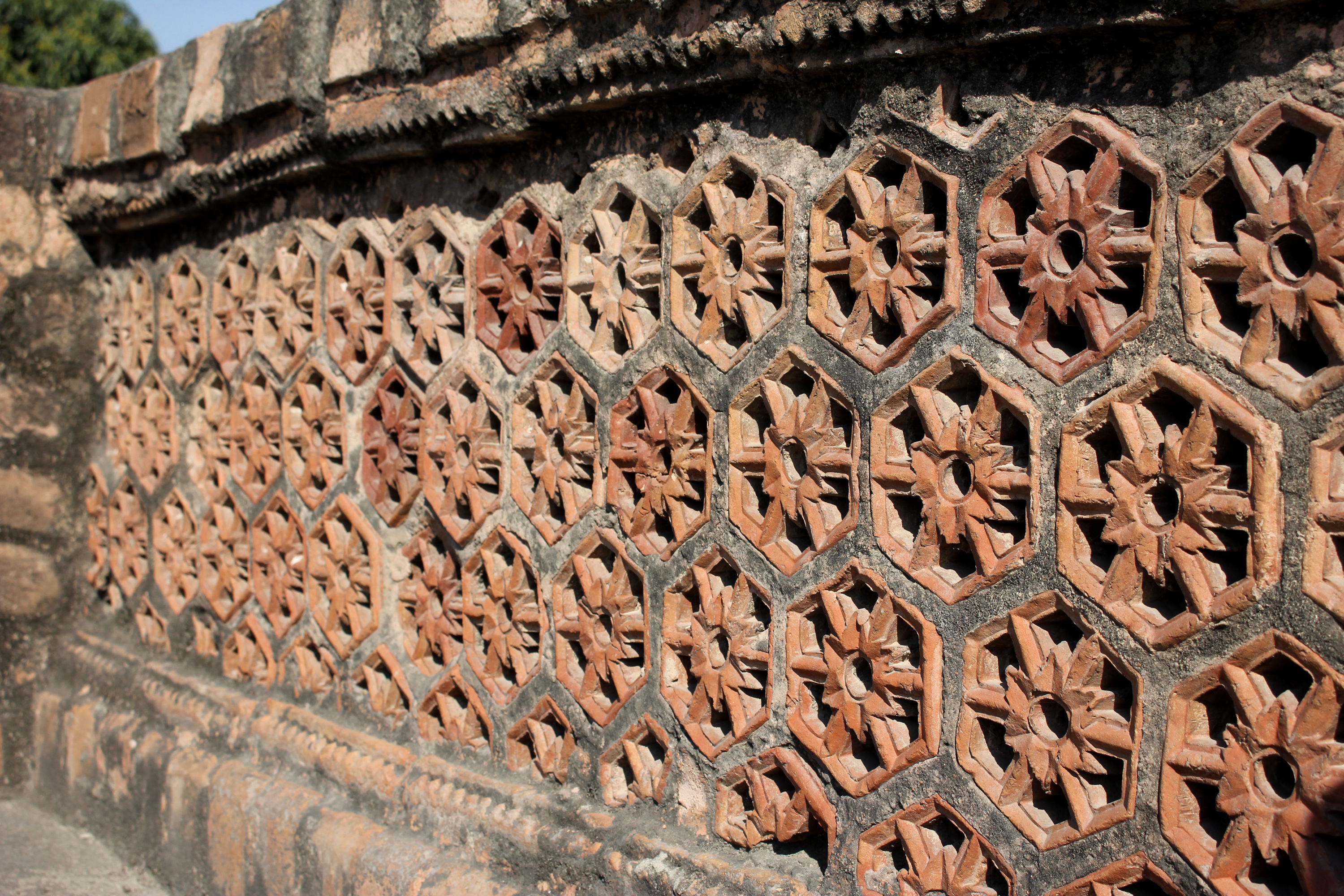

“What do you think about Lahore? Can you believe how much it’s changed?” I was asked over and over again there, as my friends listed the traffic, the crowds, the new subdivisions, the restaurants, the box stores. Yes, of course (I’ve changed too in 40 years), but really their question was rhetorical. They were telling me how their Lahore has changed, how it has been transformed from the green and pleasant place of my youth, a place of order and predictability, still basking in the afterglow of the British Raj, where we worried about contracting dysentery from improperly washed fruit or about being jostled by hideously mutilated beggars in the bazaar. Today, home, sweet home requires high walls and iron gates, reinforced by fierce dogs and quasi-uniformed men. Today, my Lahore and theirs has grown to a city of over 10 million…

— Hazel Kahan in the New York-based weekly The East Hampton Star

55 Lawrence Road, Lahore. Or as Hazel Kahan called it, home. Perhaps the last living Jewish woman to still associate Pakistan with that most hallowed of words.

And while she may have left it behind for the comfort and solitude provided by the woods of Long Island, New York, Pakistan refuses to leave her.

“When did I leave Pakistan? I left Pakistan many times. I left it every year to go to boarding school, I left when my parents moved in 1971, I left in 2011, I left in 2012 and I left in 2013,” she says. “Every single time, I never knew whether I would ever go back.”

Every single time, she did.

Having left the country along with her parents in 1971, Hazel thought she had moved on from Pakistan. “I had become occupied with other things,” she said. “I had a family, I got a PhD; I got on with my life.”

For nearly 35 years, Pakistan became a distant memory; “a dream” as she puts it. Then in 2007, her father passed away. With that came an overwhelming urge to return to her childhood home.

“My mother died quite a while back,” says Hazel, her voice occasionally cutting up on Skype. “Then, my father died and I started thinking about Lahore. Not Pakistan, Lahore.”

But she found herself alone in her association of Lahore, with no one to share and relive those fond memories with. “There was no one who understood what I meant when I said ‘Lahore’, my Lahore,” she recalls. “The only person who I could have talked to perhaps was my brother but back then we had a falling out and hadn’t talked for over 30 years.”

With time, the urge to return only increased and the more distant and ‘dreamlike’ Lahore grew, the more she knew she couldn’t stay away from it for too much longer. “55 Lawrence Road was my childhood home,” she explains. “And of course it meant a great deal to me.”

Her decision made by an overpowering and almost visceral need, Hazel soon realised travelling to Pakistan was easier said than done. “I didn’t know anyone there,” she said. “I could barely speak Urdu and then there were all these things in the media about how unsafe the country was.”

There were other hurdles in her way as well. “I was told that I wouldn’t be allowed entry into Pakistan if I had any stamps from Israel on my passport,” she adds, her voice breaking up due to weak cellular signals. “That was overcome as I applied for a new British passport and used that instead of the one that had the Israel stamps on it.”

Logistical issues, along with security fears, still needed to be sorted out though. “I booked a room in a small hotel in a residential area of Lahore,” she adds. “But the Raymond Davis incident had just taken place and there was a lot of furore in that part of the world around it.”

She got cold feet and suddenly she was not so sure about returning to a place almost forgotten; about scratching a 40-year-old itch she didn’t even realise existed until not too long ago.

But once again Lahore pulled her towards it, as if summoning her, and Hazel found herself answering its indomitable call.

In these 40 years or so, a lot had changed but Lahore, Lahore as she knew it, still retained its unmistakable identity. “As soon as I landed, I noticed that the airport was much bigger than it had been back in the day,” she says, her smile almost palpable over the voice call. “I had a clear picture of Lahore. The essence of Pakistan…it was there. I felt it immediately…it was familiar.”

A lot had changed too, as she wrote in the New York-based weekly The East Hampton Star after returning in 2011. “…still the cherished cultural heart of Pakistan but now also menacing home to the daarhiwallahs, the bearded fundamentalists in traditional shalwar kameez who easily outnumber the clean-shaven men dressed in the Western style of my day. Lahore is also home to the ‘khaki’, the unpopular and feared military.”

But before she had experienced that, she wanted to come to terms with what she was about to do. “Arriving at Lahore was such a momentous deal for me that for three days I just stayed in the hotel, not daring to go visit my old home.”

When she finally mustered up the courage to go seek the closure she desired, she realised it was easier said than done. “I arrived at the place and found the entrance guarded by two burly guards with guns. They wouldn’t let me in. I asked them to at least let me into the grounds so that I could see the house from the outside.”

They refused and she had to return to the hotel, fearing that her 7,000-mile journey had gone to waste. But the owner of the hotel had contacts who knew the affluent Rohri family who owned the property and called them to see if Hazel could be allowed in.

This time around, the two guards saluted, opened the gates and allowed her car through the front gate and, after four decades, Hazel once again walked the gardens where she grew up all those years ago.

“I was just taking it all in when someone walked out from the house and asked me if they could help me. I told them who I was and they invited me to come inside for tea when I had finished exploring outside.”

The hospitality she had known as a child came flooding back. “They patiently accompanied me from room to room, and I saw the changes they’d made since we lived there. They have a family dinner every Friday and I was the ‘guest of honour’ for this one.”

Her second home, 13 Gulberg 5, was now owned by lawyer Raza Kazim, formerly associated with the Indian National Congress before Partition and the Pakistan Peoples Party during its early stages. Through Raza’s wife, Rashida, Hazel was introduced to National College of Arts Film and TV Department Head Shireen Pasha.

Hazel joined Rashida and Pasha in filming the efforts of activist Hyder Ibrahim, who was working to resettle the flood victims of the time in a project called Resettling the Indus.

So began another journey in Pakistan, one that made her return again in 2012 and 2013. “I was overwhelmed. I had found Lahore again,” she says, once again using the word as a substitute for Pakistan, despite working in Southern Punjab rather than in the beloved city of her childhood. “Now I was involved in other peoples’ narrative.”

A narrative of the future, rather than of the past that she had come to find. But the past continues to hold a special place in Hazel’s heart and she shares it with all who care to listen. “I put together a presentation called The Other Pakistan that talked about my experiences in Pakistan and how wildly it contrasted with what we often hear. I gave five of them in the US and two in Berlin, Germany.”

Refuge in Pakistan

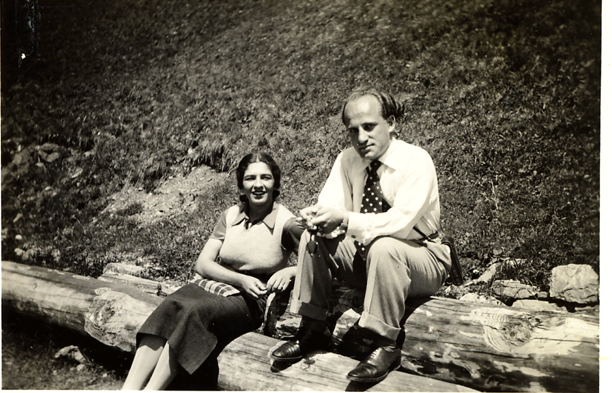

The wheels of fate that resulted in Hazel’s affiliation with Pakistan were moving on a long winding road even before she was born. “My parents were fleeing from Hitler and I will forever be grateful to Pakistan for giving us the refuge we needed back then.”

Herman Selzer and Kate Selzer were a young couple studying medicine together when they had to leave Germany, where, after 1933, Jews were not allowed to study medicine.

They made their way to Italy, where they graduated from the University of Rome. But Europe was no safe place for Jews during that time and someone in passing mentioned the crown jewel of the British Empire — India. “My father, who had completed his studies before my mother, left Rome and took a ship, I think from Naples, I can’t remember for certain, to Palestine where his parents and siblings had resettled after fleeing Europe, and then sailed to what was back then Ceylon [modern day Sri Lanka] from there. Through there they arrived in India.”

In India, Dr Herman soon found out getting work was easier said than done. “Here he was just another European doctor and they had more than enough of them. It wasn’t until he came to Lahore that he found a place to start a medical practice.”

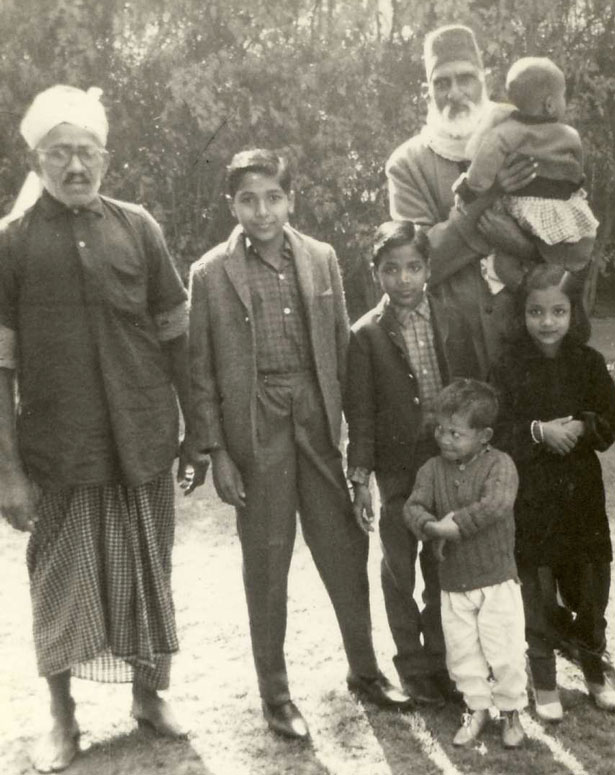

In Lahore, the Selzers had their first daughter, naming her Hazel. A son, Michael, followed soon after. But life was to take a drastic turn for the worse. “In 1941, three years after arriving in Lahore, we were sent to an internment camp near Puna because they were stateless. They were labelled ‘enemy aliens’. I was two at the time and my brother was three months old.”

Hazel as a young girl. PHOTO: HAZEL KAHAN

When they were released, nearly five years later on August 26, 1946, the movement for an independent state for the Muslims was well and truly underway but Hazel recalls there was little discrimination against her family both before and after Partition. “Everyone was very friendly towards us because we were one of the ‘people of the book’. They knew we were Jewish, but they were ok with it.”

However, having suffered a life of constant hardship due to their religion, the Selzers were not very keen on flaunting it either. “My parents were secular and we only half-celebrated the Jewish holidays.”

For more than two decades, the Selzers practiced medicine in first one and then another of their two spacious villas, and their medical reputation spread as their clinical practice grew.

But then the Six-Day War broke out. Suddenly Jews and Muslims of lands far away were enemies.

Pakistan as they knew it — hospitable, friendly, welcoming…home — was about to change drastically. “Articles started appearing in newspapers slandering my father,” recalls Hazel. “They started facing problems in banks and at other such institutions. Suddenly being Jewish mattered.”

Over the next couple of years, the sense of alienation grew and the Selzers were forced into doing what they had never even contemplated. “My parents wanted to spend the rest of their lives in Pakistan. After retiring, they planned to set up a mobile clinic and travel across the Punjab and what was back then then North-West Frontier Province.”

But they knew they couldn’t stay once relations had broken down, with Israel’s War of Attrition further increasing the Muslim-Jew divide.

And so in 1971, with heavy baggage and a heavier heart, the Selzers said farewell to the land that they had grown to love, the land that they were forever thankful to for providing them with refuge and welcome when they needed it the most — once again driven away from their home for being Jewish.

It has been 45 years since then and while relations between the two religions remain as fractious as ever across the globe, Hazel Kahan refuses to let go of the memories of yesteryears.

For her, Lahore will always be “my Lahore”.